May 27, 2024

Late April 2024 the FMA released its long-awaited Guidance, Liquidity risk management guide, (Guide) which updates and replaces the April 2020 good practice guide, Liquidity risk management. The Guide builds on at least several other prior documents of note:

Liquidity risk management (LRM) is described in the Guide as follows:

Fund liquidity is about how fund assets can be sold without negatively impacting the price of those assets or needing to secure funding (if applicable). Good management of fund liquidity is an important part of delivering fair outcomes for consumers and markets. It is critical to ensuring investors are treated equitably, and that funds perform and operate in line with the information given to investors. It also plays an important role in supporting orderly and stable markets, particularly during volatile conditions.

Scheme managers must manage withdrawal and transfer requests effectively under all market conditions. This helps to ensure investors are treated equitably. Poorly managed liquidity risk may mean some investors unfairly bear the costs of others leaving the fund, or force managers to sell fund assets for a lower price than would otherwise be the case.

(Guide, p. 4)

The description above essentially sets an objective for fund managers to be able to liquidate managed fund assets and return or transfer resulting investor money in an orderly and equitable manner, whatever the state of the markets. The Guide’s primary concern is to ensure that fund managers and their Supervisors will cooperate in implementing this objective effectively. The Guide clarifies that it “focuses on managed funds but is intended to assist all licensed managers of managed investment schemes” (Ibid.). This is a notable qualification of the Guide’s applicability for all managed investment scheme (MIS) managers. The Guide is written not just for the benefit of managers and Supervisors of retail managed funds and KiwiSaver schemes, but also the managers and Supervisors of other MIS variants such as mortgage, property, and forestry schemes. A MIS manager would be rash to assume in advance that LRM is not relevant to its own financial products.

The Guide effectively says that all MIS financial products should be viewed through the lens of LRM compatibility and that it is the legal obligation of MIS managers to do so in relation to their own financial products. Potentially every MIS manager could come under the ambit of the Guide with respect to LRM practices. After careful consideration, a MIS manager might be able to certify truthfully that its products are not subject to LRM, but if the manager is issuing managed funds, then this outcome would seem to be highly improbable. The Guide also encourages managers of wholesale schemes to consider its guidance. Furthermore, the Guide states that LRM is expected to be considered “at all stages of fund management – from fund design to day-to-day liquidity” (Ibid.). This point is highly impactful on the design and development of new managed fund products, including closed (i.e., not continuously offered) funds typically issued for large-scale real assets such as commercial property and forestry plantations.

With the Guide’s broad ambit of potential application across all MIS financial products at all stages of their life cycles, it is quite likely that some MIS managers have unknown, unrecognised, or unmanaged liquidity risks attached to their financial products. Perhaps for some MIS managers, it will be news that they have LRM to consider. A substantial annual workload lies ahead for MIS managers to comply with what the Guide prescribes. It is not just MIS managers who the Guide addresses, but also their Supervisors, who will need to adapt to the demanding new LRM environment and heighten their vigilance and activity in monitoring LRM compliance by the MIS managers they supervise.

A central regulatory plank for the Guide is the technical definition of “managed fund”, to be found in the FMC Regulations’ r 5 (1) (see Appendix 1 for full text of the regulation). The FMA expects fund managers to refer to that definition when considering their LRM obligations. The Guide sums up the regulator’s position on LRM, fund managers, and Supervisors in relation to the definition as follows:

To meet the definition of a managed fund, the managed investment products must be offered in the ordinary course of business on the basis they are continuously offered and redeemed on a basis calculated wholly or mainly on the value of the scheme property or least 80% of the scheme’s assets meet liquidity requirements in regulations. This requires sufficient liquidity management to ensure the service can be offered.

Given these clear statutory requirements, we expect all managed funds to have appropriate LRM-related policies, processes and tools. Failure to do so is likely to mean Managers and Supervisors are not meeting their statutory duties.

(Ibid., p. 5)

To drive the point home, the Guide terminates with a discussion of the FMA’s regulatory responses and concludes:

Supervisors are the frontline regulators of MIS and have primary responsibility for ensuring Managers are implementing effective LRM. Having effective LRM is integral for a Manager to show that it is meeting its statutory duties to exercise appropriate care, diligence and skill, and act in the best interests of scheme participants and treat them equitably.

In our engagements with industry, we will look to understand how Supervisors have engaged with Managers and how Managers have considered their own liquidity risks and implemented appropriate LRM in the context of the funds they manage.

(Ibid., p. 20)

Laying out a workplan for fund managers

The greatest part of the Guide is concerned with setting out what is expected of fund managers with respect to LRM. A large prospective workload for fund managers is evident, although managers should not be starting from scratch given that the FMA commenced issuing guidance on LRM back in April 2020. The Guide lists as its core content eleven “features of effective LRM” (Ibid., p.10) that it requires fund managers to respond in detail to. These features are subdivided within four categories as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Categories and features of effective LRM

|

Categories |

Features |

|

Governance and infrastructure (Features 1-3) |

Overarching framework and strategy*; Governance; Contingency plans |

|

Design, disclosure, and communication (Features 4-5) |

Product design; Disclosure and communication |

|

LRM capabilities (Features 6-10) |

Monitoring framework; Liquidity management tools*; Stress testing*; Use of leverage to adjust risk/return; Record keeping, data and systems |

|

Evaluation and review (Feature 11) |

Evaluation and review |

*Features listed for “key improvements” in the Guide (Ibid., p. 9)

The features are presented as obligatory for fund managers to consider, but optional to adopt on a “please explain” basis for any not adopted. Thus, the Guide states:

Managers must consider how these features apply to their operations and to each of their funds, and must implement them as appropriate in that context.

(Ibid., p. 10)

11.1 Both the Manager and Supervisor undertake regular evaluation and reviews of fund LRM practices to ensure these remain effective and fit for purpose. This includes looking at each of the features outlined in this guidance and completing a gap analysis of actual and expected performance.

(Ibid., p. 19)

Where Managers have not considered features in this guide, we are likely to seek explanations about how they are effectively managing their liquidity risk.

(Ibid., p. 20)

It should be noted that the eleven effective LRM features are highly cross-referential with each other, and so it could be challenging to cherry-pick from them in a manner that would enable a satisfactory explanation for not considering, let alone not implementing, any one or more of them.

In what follows concerning fund managers and their LRM-related considerations, we shall pick out a few complex points of the effective features to analyse.

Feature 1.2: “The Manager does not solely rely on LMTs to manage liquidity” (Ibid., p. 10). LMTs are deployed once a liquidity event or crisis has affected a managed fund, which means that they represent post-event reactive responses to adverse liquidity problems. The requirement of Feature 1.2 increases the ambit of LRM beyond LMTs, which otherwise might be thought of as the outer limit to LRM and raises the question as to what else could be required to comply.

Feature 2.2: “Liquidity risk reporting will include liquidity risk early-warning metrics (and supporting triggers and flags), and will account for the correlation between measures, e.g., valuation and liquidity” (Ibid., p. 11). This requirement perhaps provides at least part of the answer to complying with Feature 1.2, in that some anticipatory elements will need to be built into a fund manager’s LRM to enable proactive early initiation of liquidity event response measures prior to LMT deployment.

Feature 4.2: This feature makes plain that LRM needs to be able to cater for both “normal and stressed” market conditions (Ibid., p. 12). This requirement is important to note as LRM tends to be framed within the context of reacting to stressed market conditions, when liquidity risks are abnormally high. The Guide on this point makes it clear that LRM also needs to be demonstrably functional under non-stressed market conditions.

Feature 6.3: “The Manager has a working definition of ‘illiquid asset’ that is appropriate for the fund(s) asset composition. The definition of ‘managed fund’ in the FMC Regulations [i.e., FMC Regulations r 5(1)] provides a base-level definition that the Manager has tailored to the specific fund(s) it manages” (Ibid., p. 14). The Guide puts the onus on fund managers to work out for themselves what an illiquid asset is, but there is a very recently published resource available to assist with defining asset liquidity and illiquidity that the Guide itself refers to as a source document, namely the FSB’s Revised Policy Recommendations to Address Structural Vulnerabilities from Liquidity Mismatch in Open-Ended Funds (Policy).

Fund managers could usefully refer to the Policy’s section 3.3 Adequacy of liquidity management both at the design phase and on an ongoing basis for illumination, wherein the FSB’s Recommendation 3 is unpacked for its meaning and as a consequence categorised definitions and descriptions are provided for “liquid”, “less liquid”, and “illiquid” assets.

The Policy states:

… “liquid” assets are likely to be assets that are readily convertible into cash without significant market impact in both normal and stressed market conditions. “Less liquid” assets are those assets whose liquidity is contingent on market conditions, but they would generally be readily convertible into cash without significant market impact in normal market conditions. In stressed market conditions, they might not be readily convertible into cash without significant discounts and their valuations might become more difficult to assess with certainty. “Illiquid” assets include those for which there is little or no secondary market trading and buying and selling assets is difficult and time consuming (i.e. weeks or months, not days) even in normal market conditions. Individual transactions of “illiquid” assets may, therefore, be more likely to affect market values.

(Policy, p. 15)

The above set of definitions is then utilised in the Policy to describe categories of managed funds:

(Ibid., pp. 15-6)

In Table 2, the managed fund definitions of FMCR r. 5(1) and the Policy’s section 3.3 categorisations are compared to see how they might be matched up.

Table 2: FMCR Reg. 5(1) managed fund definition and FSB section 3.3 liquidity categorisations

|

Reg 5.1 asset type |

Reg 5.1 withdrawal period |

FSB asset liquidity equivalent |

FSB fund category equivalent |

|

Debt securities |

On demand |

Liquid |

Category 1 |

|

Debt securities |

Within 3 months |

Less liquid |

Category 2 |

|

Debt securities |

Over 3 months |

Illiquid |

Category 3 |

|

Managed investment products/MIPs |

On demand |

Liquid |

Category 1 |

|

MIPs/assets |

Within 10 days |

Less liquid |

Category 2 |

|

MIPs |

Over 10 days |

Illiquid |

Category 3 |

Plainly, blends of the above asset types with different liquidity characteristics held within a managed fund could impact how total fund liquidity is categorised, as the FSB envisages in its managed fund categories, as described in the Policy’s section 3.3.

Feature 7.2: “In assessing conditions under which LMTs might be deployed, the Manager has a graduated strategy for the use of LMTs. For example, swing pricing will usually be applied during normal market conditions. Where market conditions deteriorate, the Manager may move to deploy reactive tools, such as a notice period for redemptions and redemption gates, before progressing in a crisis to consider suspending redemptions” (Ibid., p. 15).

An implication of Feature 7.2 is that trust deeds for managed fund schemes may need to be reviewed and amended if they do not offer sufficiently “graduated” LMT responses to liquidity events. The typical trust deed allows for redemption suspension and limited borrowing as LMTs. However, Feature 7.2 reveals that redemption suspension is the last cab off the rank to deploy in the FMA’s view and that there should be prior, less drastic options available for fund managers to select from. Feature 7.2 also has implications for changes to established unit pricing practices if the likes of buy-sell spreads or swing pricing are introduced, with knock-on effects for disclosure and governing documents.

Feature 8.4: “Stress testing has an appropriate governance structure with clear objectives and upwards reporting lines, and is reviewed regularly by the oversight body (e.g., the MIS’s board, executive committee, or senior management)” (Ibid., p. 17). This feature is included in the Guide under the subheading Governance and oversight and indicates how important LRM stress testing activities rank within funds management operations. It shows that the FMA expects the relevant oversight body of a fund manager to know, understand, and receive reports on what is happening within the organisation at the fund liquidity stress testing level and undertake regular reviews of that activity.

Clearly, the Guide provides much for fund managers to get along with in perfecting their LRM practices. A useful place to start the process could be the gap analysis recommended in Feature 11.1.

A parallel workstream for Supervisors

Reprising the theme that “Supervisors are the frontline regulators for MIS”, the Guide declares that “Supervisors are responsible for overseeing Managers’ LRM” (Ibid. p. 8). A significant set of work requirements are outlined for Supervisors to follow. The core task involves deep-dive, risk-based assessments of managed funds to determine the fitness for purpose of their LRM mechanisms:

A Supervisor exercising care, diligence and skill must regularly assess a Manager’s LRM policies, processes and tools, and have an active oversight role.

This should be a fund-level, risk-based assessment with appropriately tailored frequency, scope, and intensity. It should consider whether the fund has an adequate level of resilience to liquidity stress. Supervisors can supplement their assessments by monitoring a combination of internal reports, market information and periodic surveys.

Supervisors should clearly identify the circumstances or concerns that may prompt reporting under section 203 of the FMC Act. This level of oversight is important to ensure the Supervisor can notify the FMA under section 203 of possible (or actual) contraventions of Manager obligations, and what steps (if any) the Supervisor intends to take.

(Ibid., p. 8)

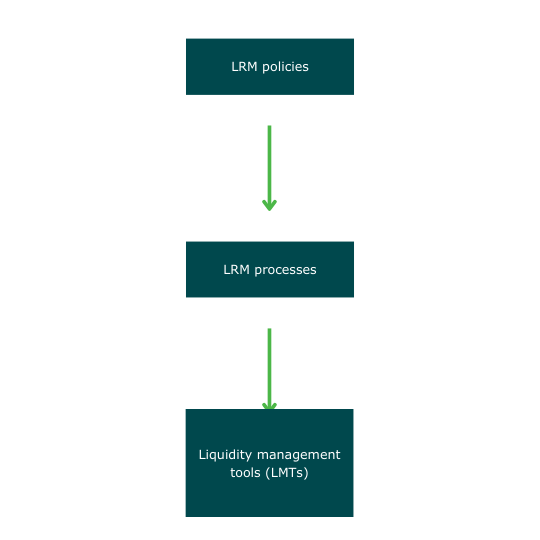

As described above, the heart of the Supervisor’s role is to focus on three LRM-related “must haves” for fund managers, as shown in Chart 1.

Chart 1: The LRM-related “must haves” hierarchy

Supervisors are expected to oversee proactively the three “must haves” across their supervised fund managers and ensure that each level of the hierarchy shown in Chart 1 is effectively integrated with the others. Ideally, the hierarchy should operate like an efficient, well-oiled machine that anticipates the potential occurrence of liquidity events and crises within asset markets and managed funds and is always poised to swing into appropriately responsive and effective action as and when required.

Supervisor assessment of LRM fitness for purpose will penetrate right down to the individual fund level. These LRM assessments must be risk-based, meaning that Supervisors will need to be able to identify liquidity risks accurately, including the types of funds and investments that could harbour problematic levels of liquidity risk that actually or potentially pose challenges for effective LRM and require timely availability of appropriate LMTs to eliminate or at least mitigate. Supervisors are additionally expected to augment their fund-centric LRM microanalysis with wider-based macroanalytics of LRM-related information sourced from their supervised fund managers - including the manager’s fund liquidity stress testing results - and other external origins.

The FMA explicitly expects Supervisors to be prepared to report under section 203 cases of possible or actual contraventions related to an issuer's LRM obligations. This expectation serves as a clear warning to fund managers that they should take their issuer obligations seriously and keep their Supervisors well-informed and up-to-date on LRM matters.

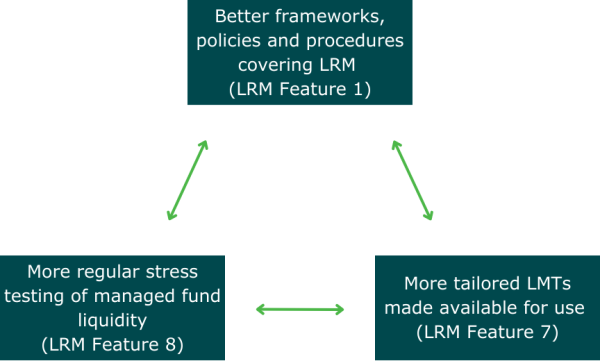

The Guide specifies that the FMA will engage directly with Supervisors as its primary means of monitoring fund managers’ LRM practices and how LRM itself relates to overall systemic risk within New Zealand’s financial markets. In particular, the FMA will expect that Supervisors are on top of the three mutually interrelated “key improvements” (Ibid., p. 9) that the regulator wants to see from fund managers in respect of LRM, as shown in Chart 2.

Chart 2: The FMA’s desired LRM key improvements

“The FMA’s Guide on LRM sets out expectations that will potentially result in substantial workloads for all fund managers and their Supervisors,” said Matthew Band, General Manager of Trustees Corporate Supervision at Trustees Executors.

“More generally, all MIS managers will need to consider the Guide with a view as to how it might apply to their own financial products, as will their Supervisors.”

“The eleven features of effective LRM as set out in the Guide collectively represent a lengthy, complex, and inter-related list of potential compliance requirements that will need to be subjected to gap analysis to help determine their applicability at the financial product level.”

“Any new MIS financial products will need to be designed to cater for LRM as appropriate.”

“Supervisors and their MIS manager clients should co-ordinate their respective regular “fit-for-purpose” evaluations and reviews of fund LRM practices, including stress testing scenarios.”

“Ideally, each year going forward from now on, MIS managers will have fully completed their own regular LRM evaluations and reviews before their Supervisors commence risk-based, fund-level LRM assessments with the benefit of access to the most current, up-to-date information.”

“To start the ball rolling, Trustees Corporate Supervision plans to engage with its MIS manager clients' LRM practices by conducting a thematic review on the subject before the end of 2024.”

“The LRM thematic review will be an opportunity for ourselves and our MIS manager clients to undertake the gap analysis that the FMA recommends in the Guide under Feature 11, Evaluation and review.”

For comment or more information, or to be added to the free email subscriber list, please contact Matthew Band at [email protected].

managed fund—

(a) means a managed investment scheme the managed investment products of which are or were—

(i) offered on the basis that, in the ordinary course of business, the products will be continuously offered and redeemed on a basis calculated wholly or mainly on the value of the scheme property; or

(ii) offered on a basis that the scheme will invest, in the ordinary course of business, at least 80% of its assets in 1 or more of the following ways:

(A) in debt securities issued by a specified bank or NBDT where the money invested is available for withdrawal immediately on request during the specified bank’s or NBDT’s normal business hours or at the end of a fixed-term period that does not exceed 3 months:

(B) in managed investment products that are redeemable on request, or within a period not exceeding 10 working days, on a basis calculated wholly or mainly on the value of the scheme property of the scheme to which those products relate:

(C) in assets where the manager can reasonably expect to realise the investment, at the market value of the assets, within 10 working days; and

(b) includes a KiwiSaver scheme, superannuation scheme, or workplace savings scheme